Company Name

Nurturing Open Space

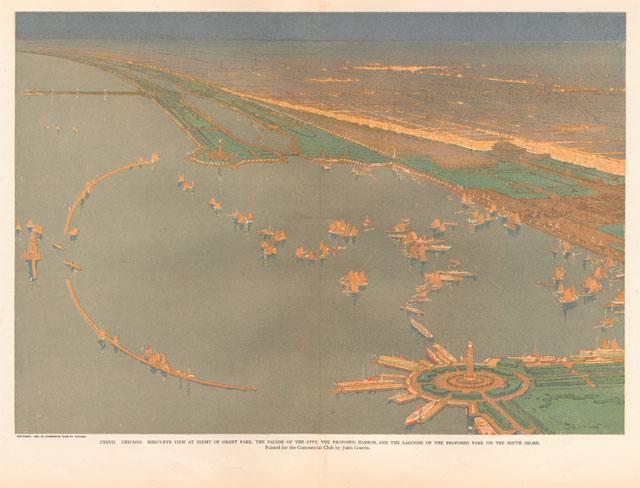

Transforming the Lakefront

Transforming Chicago's lakefront into attractive and useful public space was no small task. Railroad yards and refuse dominated a long segment of the shoreline to the south, and few people recognized the lakefront's tremendous practical and symbolic value. But Burnham and Bennett did, noting that views of the water could inspire "calm thoughts and feelings...delighting man's eye and refreshing his spirit." Like many green spaces, the lakefront could provide space for active recreation and social interaction. And, it could be a source of pride and common ground for the city's diverse population; as the plan put it, the "Lake Front by right belongs to the people."

The Plan of Chicago proposed adding cultural and educational institutions, including the Field Museum, to the lakefront near the existing Art Institute. Some park advocates, including Montgomery Ward, opposed plans to locate any institution there as it violated the promise Chicago's founders had made to keep the central lakefront "forever open, clear, and free." In a compromise, the Field and other museums were built at the far south end of Grant Park.

Over the last one hundred years, many of Burnham's ideas for the lakefront became reality. Municipal (Navy) Pier, completed in 1916, realized half of a scheme for recreational piers downtown (right). Just east of Soldier Field, Northerly Island partially fulfilled the vision of a long park-rimmed lagoon, just in time to host the 1933-34 Century of Progress International Exposition (below, left). In the 1930s, the federal Works Progress Administration funded a dizzying array of programs, from kite tournaments to concerts (below, right). This tradition continues especially at Grant Park—a hub for performances, festivals, and civic events, including Barack Obama's presidential election celebration in 2008.