Company Name

City and Region

Planning After Burnham

The Plan of Chicago had its fans and opponents, but historians agree that it transformed urban planning. Its lasting mark has less to do with the ideas in it (many were not entirely new) and more to do with its sweeping scope and persuasive presentation. Its savvy advocates solicited press coverage, organized public presentations, and distributed copies to influential politicians. They also convinced the City of Chicago to adopt the book as its official planning document. And 8th grade civics classes throughout the city studied a condensed version, known as the "Wacker Manual." The cumulative impact of these efforts convinced communities across America of the value of professional planning.

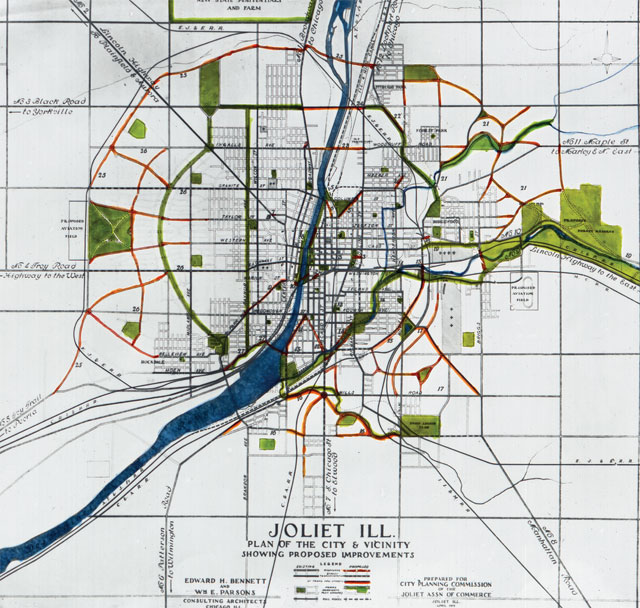

For 100 years, the Plan of Chicago has influenced places large and small. After Burnham's death in 1912, Bennett applied City Beautiful principles to Elgin, Joliet (below), Lake Forest, Waukegan, and more distant cities. Later planners wrestled with the problems of transportation and land use identified by Burnham and Bennett. In the 1930s, for example, the planners of Greendale, Wisconsin (left), emphasized green space to create what they regarded as an ideal small town.

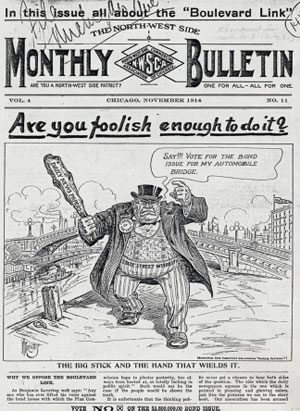

This cartoon attacks the proposal to connect the north side of the city to the Loop by turning Michigan Avenue into a bi-level bridge across the Chicago River. Opponents feared that this would divert commerce from the north side of the river to the "State Street Interests." Underneath lay a broader concern that the plan was not only insensitive to some businesses, but also neglected working people, housing, and schools.