Company Name

From City Beautiful to Green Metropolis

City and Nature

John Muir, the father of the modern conservation movement, was Burnham's contemporary. The two shared the goal of enhancing the quality of life by paying attention to the environment. While Burnham focused on improving urban places, Muir set out to conserve wilderness areas. "City" and "nature" may appear to be separate realms, but the last century has made it clear that the social and economic health of cities cannot be separated from the health of the natural environment, including our climate.

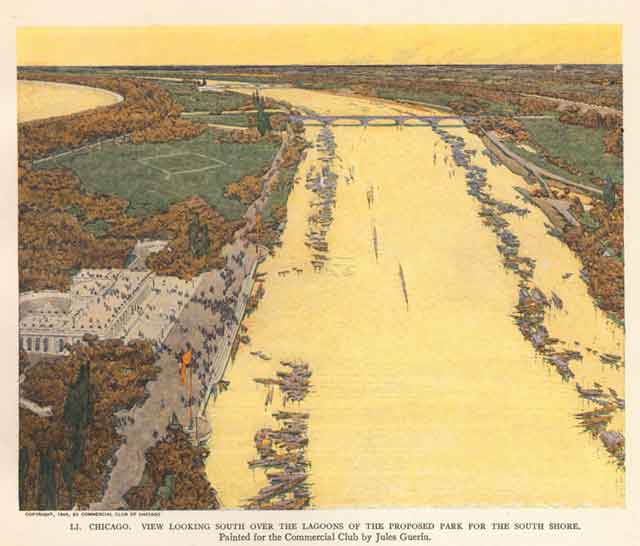

Burnham called for beautiful green spaces within the city for rest and recreation, such as the proposed lagoon-filled south shore park (top). Muir sought to protect spectacular green spaces far from the city—such as California's spectacular Yosemite Valley—for complete escape from its pressures (left). The Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, about 50 miles southwest of downtown Chicago, is a marriage of both (directly above). The land was prairie, then farmland, next military arsenal, and since 1996 has been the largest prairie restoration site in the United States. Today Midewin serves as a living laboratory for studying the region's native populations of fish, wildlife, and plants while offering recreational opportunities for area residents.

Burnham and Muir were not aware of global climate change, but it tops the list of today's environmental concerns. It is a giant puzzle for scientists, planners, and politicians. This graph offers one prediction of how Chicago's climate might change over the next 80 years if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced—a dramatic increase in the number of days over 100°F. But climate change refers not only to global temperatures. It also foresees the disruption of rainfall and water circulation, ecological systems, and agricultural production—changes that will affect life in the Chicago region for generations

to come.