Company Name

Nurturing Open Space

New Parks and Preserves

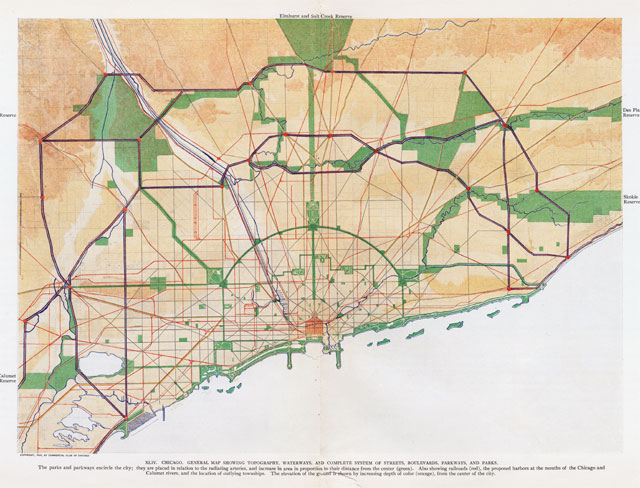

Burnham and Bennett coordinated their plans for parklands and transportation routes. Building upon existing parks and boulevards, they proposed a hundredmile green circuit: new parks would link old ones, including the lakefront drive, and in the suburbs, an outer ring of parkways would connect residents to newly created forest preserves. The planners thought about the details, too, calling for fountains and statues to adorn boulevards, and adjacent small parks to fortify the boulevards' role as "continuous playgrounds."

In Burnham's day automobiles were mostly pleasure vehicles for the well-to-do. They offered a new and enjoyable means to tour parks, nature preserves, and boulevards. The appearance of the Ford Model-T, the first "everyman's car," put many more people behind the wheel. In the coming decades, the role of the automobile in city life expanded dramatically, transforming roads designed for leisurely travel, such as Lake Shore Drive, into major commuter routes.

The suburban forest preserves established in the early 20th century were intended for recreation. Some working class Chicagoans opposed the use of public funds to create them, because they believed the lands would serve as pleasure grounds for the wealthy. Today they serve a broad spectrum of the metropolitan population, while also protecting water resources, such as wetlands, from development. Such habitats inspired-and continue to inspire- the design of new green spaces. In the early 1900s, landscape architect Jens Jensen reshaped Humboldt Park's lagoon as a prairie river.