First of three

In the church of urban planning, Daniel Burnham is a saint. Robert Moses, on the other hand, has long been viewed as the Antichrist.

For decades, Burnham’s name and his famous “Make no little plans” quote have been invoked at the drop of a hat by virtually anyone trying to promote a large project. And that’s never been truer than this year during the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Plan of Chicago of which Burnham was the primary author.

It’s as if, from the grave, the great Chicago architect-planner has been giving his imprimatur to these projects, the way Catholic bishops used to stamp books as being theologically acceptable.

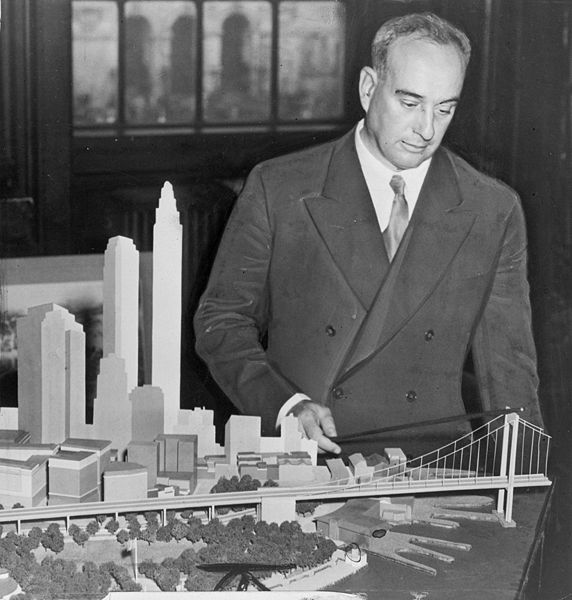

Meanwhile, Moses (left), who remade the landscape of New York City and its suburbs over the course of more than 30 years in power, has come to epitomize the height of arrogance in planning.

Meanwhile, Moses (left), who remade the landscape of New York City and its suburbs over the course of more than 30 years in power, has come to epitomize the height of arrogance in planning.

“Burnham became deified while Moses has been demonized,” says James Grossman, co-author of “The Encyclopedia of Chicago” and the vice president for research and education at the Newberry Library.

“Burnham and Moses both had [expansive] visions of what they wanted their city to look like. Burnham came off as heroic, civic-minded, a good citizen, while Moses came across as brilliant, power-hungry and despotic.”

True, there are planners who see Burnham as a top-down elitist, and, in recent years, there have been efforts to rehabilitate Moses’ reputation. Yet, the good guy/bad guy images remain.

Different personalities

Part of this has to do with the personalities of the men. Burnham was a salesman who used his charm and connections to get things done. Moses, by contrast, was a political genius who accumulated power in the nation’s greatest city to an unprecedented degree --- and suffered fools not at all.

Neither was ever elected to office.

Burnham made his name as the manager of World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 (which helped put Chicago on the world map) and then as the main writer of the 1909 document that is often called the Burnham Plan. Three years later, he died.

The Plan’s proposals were implemented --- to the extent they were implemented --- by others.

Moses was a bureaucrat extraordinaire who, by gaining the trust of successive mayors and governors, was put in charge of a dozen public agencies simultaneously and, from the 1930s to the 1960s, became a power unto himself. Indeed, Robert Caro’s majestic 1974 biography of Moses was titled “The Power Broker.”

Moses’ preferred --- and almost exclusive --- method of decision-making was by fiat.

But, during a lunchtime conversation with me, Grossman asks, “If Burnham had lived and if Burnham had been somebody who was inclined toward politics and government, would he have tried to do things the way Moses did?”

A Moses-like Burnham?

What Moses did was use his many and various powers to slam highways through New York City, slicing neighborhoods in half and displacing hundreds of thousands of people. Although he built playgrounds, parks and beaches, his greatest spending --- and his greatest social impact --- was his construction of billions of dollars of roads and bridges.

These opened Long Island to suburbanization, making it possible to live on the island and drive to and from work in Manhattan. But, quickly, each new highway became glutted with traffic. And Moses’ road-only mentality turned a blind eye to public transit.

It’s hard to see Burnham acting quite so cavalierly.

In his 2006 book “The Plan of Chicago: Daniel Burnham and the Remaking of the American City,” Carl Smith writes, “His correspondence reveals that he understood how much the actual enactment of any proposal depended not only on its inherent merits but also on attracting and shaping public opinion…Similarly, Burnham took care to see that potential skeptics and opponents, as well as local supporters, were invited to the presentations [of the Plan].”

Yet, if you look at some of Jules Guerin’s elegant watercolor renderings in the Plan, you can see a Chicago, as envisioned by Burnham, that is significantly more regimented than the city of his time --- or the city of today.

In Plate CXXII, the view of the proposed railway station west of the Chicago River shows blocks and blocks of privately owned buildings, all of the same seven-story height. It appears that Burnham is taking a page out of Baron Haussmann’s remaking of late 19th century Paris. The same can be seen in the image of the proposed Civic Center (above).

Perhaps he wasn’t really suggesting such lockstep architecture. But there it is in the Plan --- and in more than a few places.

Chicago’s Moses?

One Chicagoan, however, was a lot more like Moses than Burnham was.

“You have to add Daley to the comparison,” says Grossman. He’s referring to Mayor Richard J. Daley, the father of the present Mayor Daley and the power broker of Chicago from his 5th floor City Hall office for 20 years.

.jpg) It was the first Mayor Daley who built the expressways through Chicago, leveling churches, businesses and homes. And who wiped away an Italian-American neighborhood for the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago. And who erased whole communities to build the high-rise public housing that, recognized as social failures 40 years later, were razed with his son’s help.

It was the first Mayor Daley who built the expressways through Chicago, leveling churches, businesses and homes. And who wiped away an Italian-American neighborhood for the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago. And who erased whole communities to build the high-rise public housing that, recognized as social failures 40 years later, were razed with his son’s help.

Of course, unlike Moses, Daley had to win election. But, like Moses, he solidified his mayoral power by linking it closely to his other job --- as chairman of the Cook County Democratic Central Committee. And, like Moses, the title of his biography by Mike Royko tells the story of his power: “Boss.”

“Daley loved Chicago as a city, and I think Moses loved New York,” Grossman says.

“Both were willing to do what had to be done to help their city.”

Next: Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs: A question of power

For a print-friendly version of this post, go here.

Blog Categories

- art (14)

- civic engagement (17)

- culture (16)

- future (26)

- green legacy (15)

- history (26)

- pavilions (4)

- schools (8)

- transportation (7)