A key measure of this nation’s health is its Gross National Product. But what about its Gross National Happiness?

Don’t laugh. Gross National Happiness is the official national policy of the tiny nation of Bhutan tucked up in the eastern corner of the Himalaya Mountains.

“Every decision, every ruling, is supposedly viewed through this prism. Will this action we’re about to take increase or decrease the overall happiness of the people?” writes Eric Weiner in his 2008 book “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World.” It is “a concept that represents a profound shift in how we think about money and satisfaction and the obligation of a government to its people.”

“Every decision, every ruling, is supposedly viewed through this prism. Will this action we’re about to take increase or decrease the overall happiness of the people?” writes Eric Weiner in his 2008 book “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World.” It is “a concept that represents a profound shift in how we think about money and satisfaction and the obligation of a government to its people.”

And it has mind-opening implications for any planner who’s willing to think outside the constraints of U.S. conventional wisdom.

"The beauty of our poetry"

Unease at the Gross National Product approach to governing and planning is nothing new.

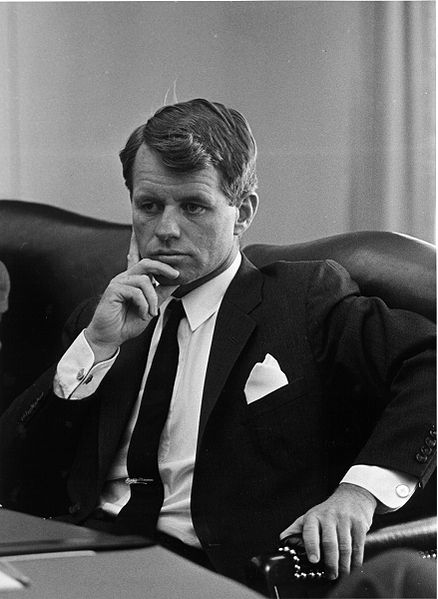

Back in March, 1968, during a speech at the University of Kansas, Robert F. Kennedy noted that the Gross National Product includes every thing, whether good or bad, that makes money --- including the manufacture of a prison lock, a nuclear missile, a cigarette and a knife used in a murder.

“Yet the Gross National Product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play,” he said. “It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it tells us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”

“Yet the Gross National Product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play,” he said. “It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it tells us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”

When it comes to planning, efficiency is often a goal --- “Will this new road get more people where they want to go with less hassle?” Or safety --- “Will this drainage requirement protect the quality of water in a nearby stream?” Or profit --- “Will the construction of a shopping mall at this corner bring more money into the village?”

But happiness? That’s not something that crops up very often in a comprehensive plan. Quality of life, I guess, is something close, but it’s a term that keeps happiness at arm’s length. After all, the question one friend is likely to ask another is: “Are you happy?” Not “How is the quality of your life?”

A fuzzy concept

Weiner acknowledges that Gross National Happiness, which has its own website, is a fuzzy concept. It’s not as if you can measure it very well --- certainly not as easily as the number of highway miles built in a year, or the number of square feet of space in a new home.

![]()

“In America, few people are happy but everyone talks about it constantly. In Bhutan, most people are happy but no one talks about it,” writes Weiner. “This is a land devoid of introspection, bereft of self-help books and woefully lacking in existential angst…The Bhutanese take the idea of Gross National Happiness seriously but by happiness they mean something very different from the fizzy, smiley face version practiced in the U.S. For the Bhutanese, happiness is a collective endeavor.”

Or as Karma Ura, Bhutanese scholar, tells him: “All happiness is relational.”

Ura, the director of the Centre for Bhutan Studies, says, “Money sometimes buys happiness. You have to break it down, though. Money is a means to an end. The problem is when you think it is an end in itself. Happiness is relationships, and people in the West think money is needed for relationships. But it’s not. It comes down to trustworthiness.”

Elements of happiness

Trust is essential for compromise --- which is a way of life in Bhutan.

On a one-lane road, Weiner finds that “passing is negotiated through a series of elaborate, poetic hand gestures…Everything in this country requires cooperation. Harvesting the crops. Passing another car on the road.

“In the West, and in the U.S. especially, we try to eliminate the need for compromise. Cars have ‘personal climate controls’ so that driver and passenger need not negotiate a mutually agreeable temperature….I wonder, though, what we lose through such conveniences. If we no longer must compromise on the easy stuff…., then what about the truly important issues? Compromise is a skill and like all skills it atrophies for lack of use.”

Another element to the Bhutanese concept of happiness seems paradoxical to a Westerner --- the recognition that we all have only a certain amount of time on the planet.

“You need to think about death for five minutes every day…,” Weiner is told. “Rich people in the West, they have not touched dead bodies, fresh wounds, rotten things. This is a problem. This is the human condition. We have to be ready for the moment when we cease to exist.”

Enough

Along those lines, happiness is also knowing when enough is enough.

“Free-market economics has brought much good to the world, but it goes mute when the concept of ‘enough’ is raised,” writes Weiner. “As the late renegade economist E.F. Schumacher put it: ‘There are poor societies which have too little. But where is the rich society that says, ‘Halt! We have enough!’ There is none.”

The U.S., of course, isn’t Bhutan. Yet, perhaps, there is something we can learn from Bhutan’s ideal of Gross National Happiness.

Maybe, as we plan our next highway or development or landfill --- whether as public officials, developers, bureaucrats or private citizens --- we can ask ourselves the question that the Bhutanese ask:

Will this action we’re about to take increase or decrease the overall happiness of the people?

For a print-friendly version of this post, go here.

Blog Categories

- art (14)

- civic engagement (17)

- culture (16)

- future (26)

- green legacy (15)

- history (26)

- pavilions (4)

- schools (8)

- transportation (7)