The most impressive image in the Plan of Chicago isn’t of Chicago.

Sure, the city is there, just a little below the center, but the watercolor by Jules Guerin puts it in its geographical context. We see virtually the entire western shoreline of Lake Michigan from Wisconsin all the way down to Chicago, and then we follow the southern lakefront across the top of Indiana over to Michigan. To the west, northwest and southwest, the land stretches on, seemingly forever.

“This is a map that has no political boundaries,” says Diane Dillon, assistant director of research and education at the Newberry Library. “It looks as if you were coming in on an airplane.”

Well, not exactly, says James Akerman, the director of the library’s cartography center. “It’s a satellite view.”

A satellite view --- just about half a century before the first satellite was launched.

Guerin’s watercolor, the frontispiece in the Plan, is also the most striking image in “Make Big Plans: Daniel Burnham’s Vision of an American Metropolis,” an exhibition created by Dillon and Akerman. Burnham was the main author of the Plan which he wrote with Edward Bennett.

The exhibit, which looks to the future as well as the past, is now on view simultaneously at 66 libraries and other locations from Kenosha, Wisc., to Michigan City, Ind., and even as far away as Springfield. A digital version is also available online.

I’m standing with Dillon and Akerman in front of a reproduction of the Guerin illustration in the Newberry where “Make Big Plans” was on show alongside an exhibit of Burnham’s planning for the Philippines before closing there on July 15.

“There really isn’t anything that precedes [the Plan] as a regional plan,” Akerman is saying.

No lines

The lack of boundaries in the Guerin image is a recognition that, regardless of the arbitrary lines that humans put on maps, they don’t exist in the physical landscape. There is no Chicago or Hinsdale or Waukegan --- no way for one part of that landscape to separate itself from all the rest. Every place is part of the same broad fabric.

Indeed, the Dillon-Akerman exhibit quotes Burnham and Bennett as writing that “there exist between this city and outlying towns within a certain radius vital and almost organic relations.”

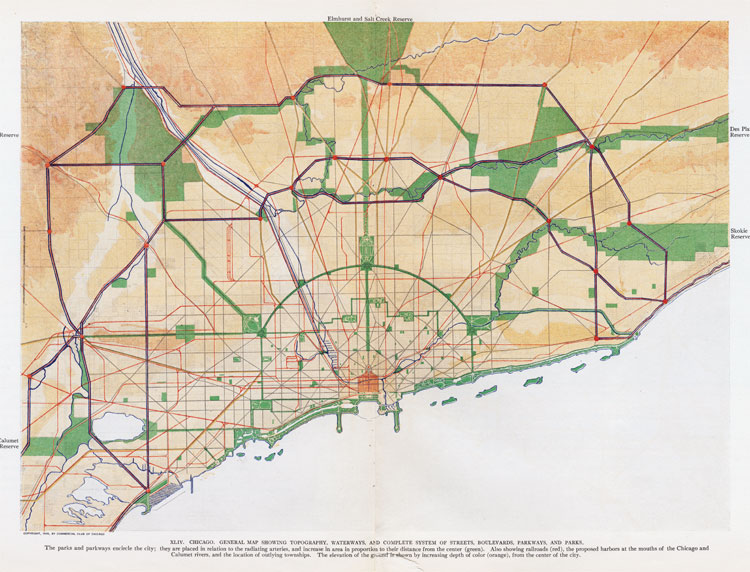

When the Burnham Plan was published on July 4, 1909, it was unique in its aggressively regional vision. The authors plotted out a regional highway system (that looks much like today’s expressway-tollway network). They designed a regional freight movement scheme. They called for the establishment of regional forest preserves.

“Burnham writes compellingly in the Plan that now is the time to obtain this land,” says Dillon. “He had a real sense of urgency that’s pretty eloquent.”

And visionary.

There had been plans for in-city parks, such as Central Park in New York City (completed in 1873) and the Fens in Boston (created in 1882). But the Burnham Plan was the first to recognize the need for parkland in suburban areas that had yet to be developed.

“The idea of setting aside green space on that scale is new,” says Akerman.

Bottom-up and top-down

Even so, despite the Plan’s regional vision, its only site-specific proposals had to do with Chicago --- and almost all with the city’s downtown.

One example is illustrated by another Guerin watercolor reproduced in the exhibit, a view of a monumental Civic Center and plaza that Burnham wanted to be built at Halsted and Congress Streets. While most of the Plan’s proposals were implemented to one extent or another, the Civic Center is one that never became reality.

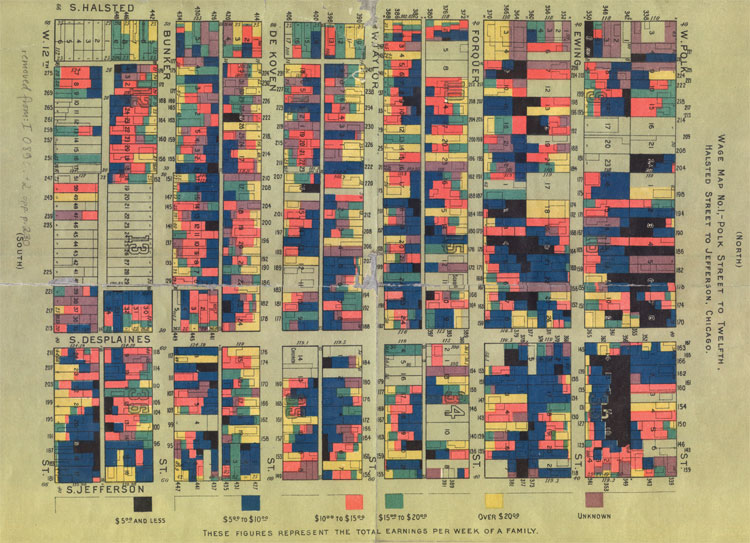

This Guerin watercolor is only a few feet away from another image of that same neighborhood --- a brilliantly colored Hull House map showing house-by-house the income level of the residents of 12 city blocks.

It’s a canny dramatization of the poverty of the neighborhood and provides a sharp contrast to the Guerin art --- and to the Burnham Plan.

It’s a canny dramatization of the poverty of the neighborhood and provides a sharp contrast to the Guerin art --- and to the Burnham Plan.

Jane Addams and her colleagues at Hull House produced maps like this, created with data collected by the inhabitants, in an effort “to improve the neighborhood for the residents who lived there,” says Dillon. Addams was taking a bottom-up approach to city planning.

The Plan of Chicago was very much a top-down document, even a trickle-down document.

As the “Make Big Plans” exhibit notes, “Advocates of the City Beautiful Movement, exemplified by the Plan of Chicago, took an aesthetic approach to solving these ills: they believed a more attractive and efficient physical environment would improve the social environment.” So life for the poor and the rest of the citizenry would be better if the place where they lived was more orderly and beautiful.

And one other important consideration during a time when the powers-that-be were worried about civil unrest and potential rebellion: A healthier, happier populace would be less likely to cause trouble.

As Dillon notes, “Burnham thought, if you improve these aspects of the urban environment, people will behave better.”

(Next: Librarians talk about “Make Big Plans”)

For a print-friendly version of this post, go here.

Blog Categories

- art (14)

- civic engagement (17)

- culture (16)

- future (26)

- green legacy (15)

- history (26)

- pavilions (4)

- schools (8)

- transportation (7)