Someday, fairly soon, a 10-year-old girl will look out over a vast panorama of prairie grasses and travel back hundreds of years to a time when the landscape was unplowed and unpaved. She will imagine herself as a young Native American or perhaps the daughter of a German immigrant heading west for opportunity.

Standing there, in the Learning Center at the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie in Wilmington, she won’t know how important Nov. 5, 2009 was in making that journey of the imagination possible.

.jpg)

Someday, five friends on a bicycling vacation will pedal down Chicago’s lakefront, cut west through the small village of Burnham, down the Burnham Greenway, along the Pennsy Trail and, eventually, over to the 500-mile Grand Illinois Trail.

But, as they head west across the middle of the state to the Mississippi River, they won’t realize that Nov. 5, 2009 was a turning point in making all of those connections possible.

Nov. 5, 2009 --- yesterday --- was a key moment in the long history of environmentalism in the Chicago metropolitan region.

It was a key moment in the growing movement to safeguard and nurture the green infrastructure that underpins all life here --- the mosaic of natural areas that includes woodlands, savannas, prairies, wetlands, lakes, streams, rain gardens and native landscaping. And it was a key moment in the effort to make it easier for the eight million people of the region to get to the natural world for beauty, exercise and respite from the intensity of urban living.

The occasion was “Our Green Metropolis: The Next 100 Years,” a gathering of conservationists and other environmental activists, sponsored by the Burnham Plan Centennial at the Spertus Museum.

The event honored the progress made on behalf of 21 “green legacy” projects throughout the region, highlighted as part of this year’s celebration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Plan of Chicago, written by Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett. Not only did that document change the face of Chicago, but it was visionary in its call to turn the city’s 30-mile lakefront into parkland and to begin amassing large tracts of open green areas in what today is the 68,000-acre Cook County Forest Preserve District.

That Plan “redefined the relationship between the urban and the natural environments, the idea that access to nature was necessary to urban living and had to be provided for conscientiously,” George Ranney, the co-chair of the Centennial, told the audience of more than 300.

In celebrating the Plan’s centennial, the aim has been “to build momentum, to put more wind in the sails of the conservation community…The best way to do that, we thought, was to set clear goals and to tie them to firm deadlines,” added Ranney, the president and CEO of Chicago Metropolis 2020.

So, for the 21 “green legacy” projects --- ranging from new parks along abandoned elevated railroad right-of-ways to the protection of rare black oak savannas --- targets were set, partnerships were formed and commitments were vowed. And, during the 12 months, progress was made.

As the centennial year unfolded, Nov. 5, 2009 developed into an important deadline.

Conservationists across the region strove to achieve important breakthroughs in “green legacy” projects and other initiatives to announce at the “Our Green Metropolis” gathering.

And they succeeded.

Great vistas

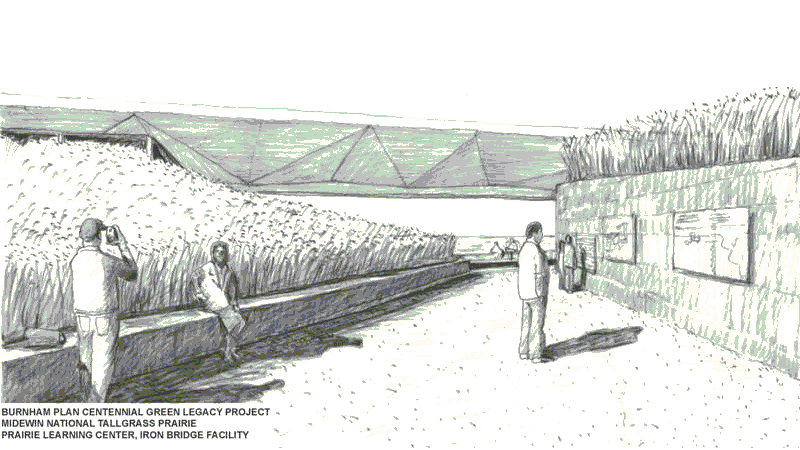

Marta Witt from the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie announced that the U.S. Forest Service has chosen a design by Wheeler Kearns, a Chicago architecture firm, for a new Prairie Learning Center.

The Prairie, a sweeping 19,000-acre landscape on the former site of the Joliet Arsenal, is the largest prairie restoration project ever attempted east of the Mississippi and the largest protected open space in the region, covering more land than Evanston, Skokie, Morton Grove and Wilmette combined.

But it’s been hard for anyone to see it. That’s a problem that the two-location learning center will solve.

The innovative design employs rammed earth support walls which uses an ancient technology to create an intimate connection with the land. The two locations will be set into the landscape in ways to give visitors the ability to scan across great vistas of the prairie.

A lakefront step

State Rep. Barbara Flynn Currie announced that she will join in introducing a bill in February to transfer about 100 acres of lakefront property from the Illinois International Port District to the Chicago Park District.

This land transfer is essential to an effort to create parkland on the only four miles of Chicago’s lakefront that aren’t now open to public use. Two miles are on the Far North Side, and two miles are on the Far South Side.

The bill, which will be co-sponsored by State Senate President John Cullerton and State Rep. Marlow Colvin, involves land known as Iroquois Landing, the site of a former steel mill just north of Calumet Park at about 95th Street.

Like much of the “green legacy” efforts through the year and the other progress announced at the event, the transfer of this land is one of many steps that need to be taken to reach the ultimate goal of a single lakefront park running the entire length of Chicago from Evanston to Indiana.

Each step, of course, is important.

Nature amid industry

Currie also announced that her bill most probably will also take a small but important step on behalf of another “green legacy” project, the creation of the Calumet Open Space Reserve nearby.

These natural areas, in the midst of one of the most industrialized sections of an American city, cover 4,800 acres of diverse wetlands that are home to more than 2,200 species of animals. Among those are 200 species of birds that nest or migrate through these wetlands.

Progress

Sometimes, it’s progress simply to start figuring out how bad and good things are. At other times, it’s progress simply to set a goal to work toward.

David Pope, the village president of Oak Park and the co-chair of the environmental committee of the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus, announced at “Our Green Metropolis” that the Caucus will conduct a new initiative in 2010 as part of its Greenest Region Compact.

The purpose, Pope said, will be to look at how local municipalities are doing in terms of protecting the environment on a variety of measures. This effort, he said, will provide “an environmental baseline” so that planners will know on which issues improvement is most needed.

Melinda Pruett-Jones, executive director of Chicago Wilderness, announced that her group has set a goal of protecting in a variety of ways the natural character of 1.8 million acres of interconnected lands and waters in this region by the year 2060.

Her group, an alliance of conservation organizations throughout the metropolitan region promoting the benefits of biodiversity, recognizes that, within the 1.8 million acres, many areas are already developed. In such places, Pruett-Jones said, “protecting the green infrastructure can be as simple as promoting native landscaping, rain gardens and green roofs.”

Elsewhere, she noted, it will be important to set aside open space as nature reserves and steward this landscape to ensure its health and resiliency.

Nature and political boundaries

John Rogner, an assistant director of the Illinois Natural Resources Department, announced that Gov. Pat Quinn has asked the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to study the feasibility of establishing the Hack-ma-tack National Wildlife Refuge on 10,000 acres in McHenry County in northern Illinois and Walworth County in southern Wisconsin.

“The region’s natural green infrastructure doesn’t recognize political boundaries,” he noted.

Officials from Wisconsin and Illinois have been meeting with preservationists to protect this dramatic glacial landscape and a diverse ecosystem now under threat by the rapid development in those two counties.

The “linchpin”

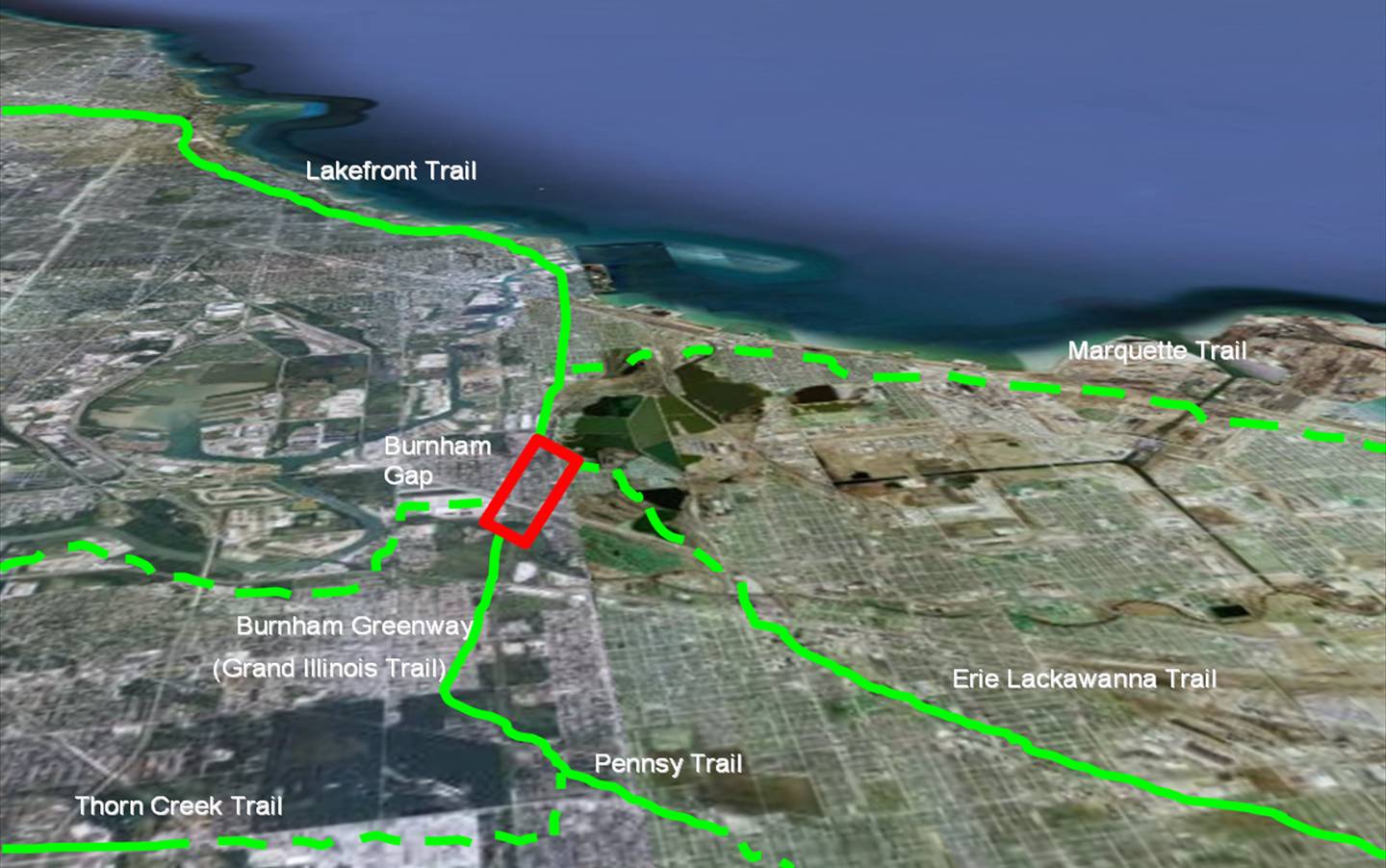

Rogner also joined with Steve Solomon, president of the Exelon Foundation, to announce a breakthrough in the interconnection of six present and planned trails throughout the region and across Northern Illinois.

In the 11-mile Burnham Greenway, there is a two-mile gap where the greenway would cross the border of the Far Southeast Side of Chicago and the southern suburb of Burnham (which is named for Telford Burnham who laid out the property lines for the town in 1883, not for the much more famous Daniel Burnham).

Closing this gap in the Burnham Greenway, just west of Wolf Lake, would create a key junction for five present and planned trails of regional, state and national significance, including the 500-mile Grand Illinois Trail which runs between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River.

“In the metropolitan region, it’s the most important gap that, if completed, would make all these things possible. It doesn’t complete the whole system, but this is the linchpin,” according to Openlands executive director Jerry Adelmann.

The breakthrough is that, within the next few weeks, the Natural Resources Department and Commonwealth Edison will form a partnership to develop recreational green space on a one-mile segment of the gap through Commonwealth Edison property.

Solomon said that this partnership will be a model that will “help close [trail] gaps in other locations where Com Ed owns property.”

Nov. 5, 2009

Many steps on many fronts.

“Our Green Metropolis” was a celebration of what has been accomplished, but even more it was a moment to check the region’s environmental agenda and realize how much more needs to be done.

A few years from now, that 10-year-old girl will be gazing across the vast prairie vistas at Midewin. At a later date, those cyclists will zip through what was once called the Burnham Gap.

These will happen because of what occurred on Nov. 5, 2009 --- but only if those efforts continue year-in and year-out.

Someday, maybe all of these projects will be completed. Maybe, someday, future generations will look back to this time to recognize the hard work and commitment that was invested by this region in saving its natural areas, its green infrastructure.

But there will never come a day when the work of protecting our natural world is finished.

This natural world is our home. By nurturing it, we live better.

Our lives are less --- much less --- if we ignore it.

For a print-friendly version of this post, go here.

Blog Categories

- art (14)

- civic engagement (17)

- culture (16)

- future (26)

- green legacy (15)

- history (26)

- pavilions (4)

- schools (8)

- transportation (7)